|

RSS:

Beatles.ru в Telegram:

|

|

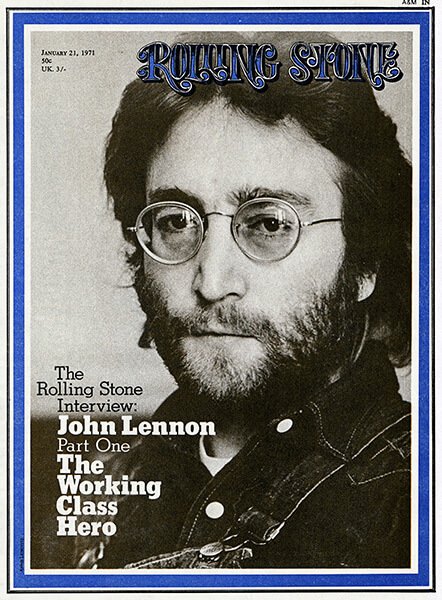

John Lennon - Part One: The Working Class Hero

In a raw, candid interview, he talks about Beatles’ breakup, Yoko, and why ‘John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band,’ is “the best thing I’ve ever done” This interview took place in New York City on December 8th, shortly after John and Yoko finished their albums in England. They came to New York to attend to the details of the release of the album, to make some films, and for a private visit. What do you think of your album?

I think it’s the best thing I’ve ever done. I think it’s realistic and it’s true to the me that has been developing over the years from my life. “I’m a Loser,” “Help,” “Strawberry Fields,” they are all personal records. I always wrote about me when I could. I didn’t really enjoy writing third person songs about people who lived in concrete flats and things like that. I like first person music. But because of my hang-ups and many other things; I would only now and then specifically write about me. Now I wrote all about me and that’s why I like it. It’s me! And nobody else. That’s why I like it. It’s real, that’s all. I don’t know about anything else, really, and the few true songs I ever wrote were like “Help” and “Strawberry Fields.” I can’t think of them all offhand. They were the ones I always considered my best songs. They were the ones I really wrote from experience and not projecting myself into a situation and writing a nice story about it. I always found that phony, but I’d find occasion to do it because I’d be so hung up, I couldn’t even think about myself. On this album, there is practically no imagery at all.

Because there was none in my head. There were no hallucinations in my head. There are no “newspaper taxis.”

Actually, that’s Paul’s line. I was consciously writing poetry, and that’s self-conscious poetry. But the poetry on this album is superior to anything I’ve done because it’s not self-conscious, in that way. I had least trouble writing the songs of all time. Yoko: There’s no bullshit. John: There’s no bullshit. The arrangements are also simple and very sparse.

Well, I’ve always liked simple rock. There’s a great one in England now, “I Hear You Knocking.” I liked the “Spirit in the Sky” a few months back. I always liked simple rock and nothing else. I was influenced by acid and got psychedelic, like the whole generation, but really, I like rock and roll and I express myself best in rock. I had a few ideas to do this with “Mother” and that with “Mother” but when you just hear, the piano does it all for you, your mind can do the rest. I think the backings on mine are as complicated as the backings on any record you’ve ever heard, if you’ve got an ear. Anybody knows that. Any musician will tell you, just play a note on a piano, it’s got harmonics in it. It got to that. What the hell, I didn’t need anything else. How did you put together that litany in “God”?

What’s “litany?” “I don’t believe in magic,” that series of statements.

Well, like a lot of the words, it just came out of me mouth. “God” was put together from three songs almost. I had the idea that “God is the concept by which we measure pain,” so that when you have a word like that, you just sit down and sing the first tune that comes into your head and the tune is simple, because I like that kind of music and then I just rolled into it. It was just going on in my head and I got by the first three or four, the rest just came out. Whatever came out. When did you know that you were going to be working towards “I don’t believe in Beatles”?

I don’t know when I realized that I was putting down all these things I didn’t believe in. So I could have gone on, it was like a Christmas card list: where do I end? Churchill? Hoover? I thought I had to stop. Yoko: He was going to have a do it yourself type of thing. John: Yes, I was going to leave a gap, and just fill in your own words: whoever you don’t believe in. It had just got out of hand, and Beatles was the final thing because I no longer believe in myth, and Beatles is another myth. I don’t believe in it. The dream is over. I’m not just talking about the Beatles, I’m talking about the generation thing. It’s over, and we gotta – I have to personally – get down to so-called reality. When did you become aware that that song would be the one that is played the most?

I didn’t know that. I don’t know. I’ll be able to tell in a week or so what’s going on, because they [the radio] started off playing “Look At Me” because it was easy, and they probably thought it was the Beatles or something. So I don’t know if that is the one. Well, that’s the one; “God” and “Working Class Hero” probably are the best whatevers – sort of ideas or feelings – on the record. Why did you choose or refer to Zimmerman, not Dylan.

Because Dylan is bullshit. Zimmerman is his name. You see, I don’t believe in Dylan and I don’t believe in Tom Jones, either in that way. Zimmerman is his name. My name isn’t John Beatle. It’s John Lennon. Just like that. Why did you tag that cut at the end with “Mummy’s Dead”?

Because that’s what’s happened. All these songs just came out of me. I didn’t sit down to think, “I’m going to write about Mother” or I didn’t sit down to think “I’m going to write about this, that or the other.” They all came out, like all the best work that anybody ever does. Whether it is an article or what, it’s just the best ones that come out, and all these came out, because I had time. If you are on holiday or in therapy, wherever you are, if you do spend time . . . like in India I wrote the last batch of best songs, like “I’m So Tired” and “Yer Blues.” They’re pretty realistic, they were about me. They always struck me as – what is the word? Funny? Ironic? – that I was writing them supposedly in the presence of guru and meditating so many hours a day, writing “I’m So Tired” and songs of such pain as “Yer Blues” which I meant. I was right in the Maharishi’s camp writing “I wanna die . . . ” “Yer Blues,” was that also deliberately meant to be a parody of the English blues scene?

Well, a bit. I’m a bit self-conscious – we all were a bit self-conscious and the Beatles were super self-conscious people about parody of Americans which we do and have done. I know we developed our own style but we still in a way parodied American music . . . this is interesting: in the early days in England, all the groups were like Elvis and a backing group, and the Beatles deliberately didn’t move like Elvis. That was our policy because we found it stupid and bullshit. Then Mick Jagger came out and resurrected “bullshit movement,” wiggling your arse. So then people began to say the Beatles were passé because they don’t move. But we did it as a conscious move. When we were younger, we used to move, we used to jump around and do all the things they’re doing now, like going on stage with toilet seats and shitting and pissing. That’s what we were doing in Hamburg and smashing things up. It wasn’t a thing that Pete Townshend worked out, it is something that you do when you play six or seven hours. There is nothing else to do: you smash the place up, and you insult everybody. But we were groomed and we dropped all of that and whatever it was that we started off talking about, which was what singing . . . what was it? What was the beginning of that? Was “Yer Blues” deliberate?

Yes, there was a self-consciousness about singing blues. We were all listening to Sleepy John Estes and all that in art school, like everybody else. But to sing it, was something else. I’m self-conscious about doing it. I think Dylan does it well, you know. In case he’s not sure of himself, he makes it double entendre. So therefore he is secure in his Hipness. Paul was saying, “Don’t call it ‘Yer Blues,’ just say it straight.” But I was self-conscious and I went for “Yer Blues.” I think all that has passed now, because all the musicians . . . we’ve all gotten over it. That’s self-consciousness. Yoko: You know, I think John, being John, is a bit unfair to his music in a way. I would like to just add a few things . . . like he can go on for an hour or something. One thing about Dr. Janov, say if John fell in love, you know he is always falling in love with all sorts of things, from the Marharashi to all what not. [John and Yoko went through four months of intensive therapy with Dr. Arthur Janov, author of ‘The Primal Scream’ (Putnam’s), in Los Angeles, June through September of this year. In October they returned to England, where they made their new albums. “Having a primal,” or “primaling,” is an extremely intense type of re-living/acting-out experience, around which many of Janov’s theories are based.] John: Nobody knows there is a point on the first song on Yoko’s track where the guitar comes in and even Yoko thought it was her voice, because we did all Yoko’s in one night, the whole session. Except for the track with Ornette Coleman from the past that we put on to show people that she wasn’t discovered by the Beatles and that she’s been around a few years. We got stuff of her with Cage, Ornette Coleman . . . we are going to put out “Oldies But Goldies” next for Yoko. I’ll play it again and talk about it later. Yoko: There is this thing that he just goes on falling in love with all sorts of things. But it is like he fell in love with some girl or something and he wrote this song. Who he fell in love with is not very important, the outcome of the song itself is important. That is very important. For instance, you have to say that a song like “Well, Well, Well” is connected with Primal therapy or the theory of Primal Therapy.

Why? The screaming.

No, no. Listen to “Cold Turkey.” Yoko: He’s screaming there already. John: Listen to “Twist and Shout.” I couldn’t sing the damn thing I was just screaming. Listen to it. Wop-Bop-a-loo-bop-a-Wop-bam-boom. Don’t get the therapy confused with the music. Yoko’s whole thing was that scream. “Don’t Worry, Kyoko” was one of the fuckin’ best rock and roll records ever made. Listen to it, and play “Tutti Fruitti.” Listen to “Don’t Worry, Kyoko” on the other side of “Cold Turkey.” I’m digressing from mine, but if somebody with a rock-oriented mind could possibly hear her stuff, you’ll see what she’s doing. It’s fantastic, you know. It’s as important as anything we ever did, and it is as important as anything the Stones or Townshend ever did. Listen to it, and you’ll hear what she is putting down. On “Cold Turkey” I’m getting towards it. I’m influenced by her music 1000 percent more than I ever was by anybody or anything. She makes music like you’ve never heard on earth. And when the musicians play with her, they’re inspired out of their skulls. I don’t know how much they played her record later. We’ve got a cut of her from the Lyceum in London, 15 or 20 musicians playing with her, from Bonnie and Delaney and the fucking lot. We played the tracks of it the other night. It’s the most fantastic music I’ve ever heard. They’ve probably gone away and forgotten all about it. It’s fantastic. It’s like 20 years ahead of its time. Anyway, back to mine. You once said about “Cold Turkey”: “That’s not a song, that’s a diary.”

So is this, you know. I announced “Cold Turkey” at the Lyceum saying, “I’m going to sing a song about pain.” So pain and screaming was before Janov. I mean Janov showed me more of my own pain. I went through therapy with him like I told you and I’m probably looser all over. Are you less paranoid now?

No. Janov showed me how to feel my own fear and pain, therefore I can handle it better than I could before, that’s all. I’m the same, only there’s a channel. It doesn’t just remain in me, it goes round and out. I can move a little easier. What was your experience with heroin?

It just was not too much fun. I never injected it or anything. We sniffed a little when we were in real pain. We got such a hard time from everyone, and I’ve had so much thrown at me, and at Yoko, especially at Yoko. Like Peter Brown in our office – and you can put this in – after we come in after six months he comes down and shakes my hand and doesn’t even say hello to her. That’s going on all the time. And we get into so much pain that we have to do something about it. And that’s what happened to us. We took “H” because of what the Beatles and others were doing to us. But we got out of it. Yoko: You know he really produced his own stuff. Phil is, as you know, well-known about as a very skillful sort of technician with electronics and engineering. John: But let’s not take away from what he did do, which expended a lot of energy and taught me a lot, and I would use him again. Like what?

Well, I learned a lot on this album, technically. I didn’t have to learn so much before. Usually Paul and I would be listening to it and we wouldn’t have to listen to each individual sound. So there are a few things I learned this time, about bass, one track or another, where you can get more in and where I lost something on a track and some technical things that irritated me finally. But as a concept and as a whole thing, I’m pleased, yes. That’s about it, really. If I get down to the nitty gritty, it would drive me mad, but I do like it really. When you record, do you go for feeling or perfection of the sound?

I like both. I go for feeling. Most takes are right off and most times I sang it and played it at the same time. I can’t stand putting the backing on first, then the singing, which is what we used to do in the old days, but those days are dead, you know. It starts off with bells: why?

Well, I was watching TV as usual, in California, and there was this old horror movie on, and the bells sounded like that to me. It was probably different, because those were actually bells slowed down that they used on the album. They just sounded like that and I thought oh, that’s how to start “Mother.” I knew “Mother” was going to be the first track so . . . You said that you wrote most of the songs in California?

Well, actually some of it. Actually I wrote “Mother” in England, “Isolation” in England and a few more. I finished them off in California. You will have to push me if you want more detail. “Look At Me” was written around the Beatles’ double album time, you know, I just never got it going, there are a few like that lying around. You said that this would be the first “Primal Album.”

When did I say that? In California. Have you gone off it?

I haven’t gone off it, it is just that “Primal” is like another mirror, you know. Yoko: He is sort of like any artist, because he really wants to be honest to himself and to the album, I suppose. What he does is just patching up something that is sort of interesting – so-so, or something. He really puts himself in it, his life in it, you know, and so, like when he went to India, he was inflluenced by the Maharishi. John: It’s really like, you know, writers take themselves to Singapore to get the atmosphere. So wherever I am. In that way it is sort of a “Primal” album. It’s like George’s is the first “Gita” album. Yoko: It’s that relevant. The Primal Scream is a mirror and he was looking at the mirror. When you came out to San Francisco, you wanted to take an advertisement to say, “This Is It!”

I think that is something people will go through at the beginning of that therapy, because you are so astounded with what you find out about yourself. You think, well, surely this is something, because it happens to you, and this must be the first time that it happened. And, it was that we wanted to come. I need a reason for going somewhere – otherwise I’m too nervous, so I calm myself. So that was a good way of coming to San Francisco to see you. Then I have an objective: “I’m going to do an act and this is what we are coming to do.” And we settle down and we just talk. I still think that Janov’s therapy is great, you know, but I don’t want to make it into a big Maharishi thing. You were right to tell me to forget the advert, and that is why I don’t even want to talk about it too much, if people know what I’ve been through there, and if they want to find out, they can find out, otherwise it turns into that again. You don’t want people to think that this is the single thing to do.

I don’t think anything else would work on me. But then of course, I’m not through with it; it’s a process that is going on. We primal almost daily. You see, I don’t really want to get this big Primal thing going because it is so embarrassing. The thing in a nutshell: primal therapy allowed us to feel feelings continually, and those feelings usually make you cry. That’s all. Because before, I wasn’t feeling things, that’s all. I was blocking the feelings, and when the feelings come through, you cry. It’s as simple as that, really. Do you think the experience of therapy helped you become a better singer?

Maybe. Do you think your singing is better on this album?

It’s probably better because I have the whole time to myself, you know. I mean I’m pretty good at home with the tapes. This time it was my album and it used to get a bit embarrassing in front of George and Paul, because we know each other so well. We used to be a bit supercritical of each other, so we inhibited each other a lot. And now I have Yoko there, and Phil there, alternatively and together, who sort of love me so that I can perform better, and I relaxed. I’ve got a whole studio at home now, and I think it will be better next time, because that is even less inhibiting than going to E.M.I. It’s like that, but the looseness of the singing was developing on “Cold Turkey” from the experience of Yoko’s singing. You see, she does not inhibit her throat. It says on the album that Yoko does wind?

Yes. Well, she plays wind, she played atmosphere. She has a musical ear, and she can produce rock and roll. She can produce me, which she did for some of the tracks. I’m not going to start saying that she did this and he did that. But when Phil couldn’t come at first . . . you don’t have to be born and bred in rock, she knows when a bass sound is right, and when a guy is playing out of rhythm and when the engineer – she had a bit of trouble – the engineer thinks well, who the hell is this? What does she know about it? So, she did that for me. “Working Class Hero” sounds like an early Dylan song.

Anybody that sings with a guitar and sings about something heavy would tend to sound like this. I’m bound to be influenced by those, because that is the only kind of real folk music I really listen to. I never liked the fruity Judy Collins and Baez and all of that stuff. So the only folk music I know is about miners up in Newcastle, or Dylan. In that way I would be influenced, but it doesn’t sound like Dylan to me. Does it sound like Dylan to you? Only in the instrumentation.

That’s the only way to play. I never listen that hard to him. Did you put in “fucking” deliberately on “Working Class Hero?”

No. I put it in because it fit. I didn’t even realize that there were two in the song until somebody pointed it out. When I actually sang it, I missed a verse which I had to add in later. You do say “fucking crazy”‘ that is how I speak. I was very near to it many times in the past, but, I would deliberately not put it in, which is the real hypocrisy, the real stupidity. What is November 5th?

In England it’s the day they blew up the Houses of Parliament so we celebrate by having bonfires every November 5th, Guy Fawkes Day. It just was an ad lib: it was about the third take, and I got to remembering, and it begins to sound like Frankie Laine, you know, when you sing, (sings) “Remember the Fifth of November.” I just broke up, and it went on for about another seven or eight minutes. We started ad libbing and goofing about, but then I cut it there and just exploded, it was a good joke. Haven’t you ever heard of Guy Fawkes? I thought it was just poignant that we should blow up the Houses of Parliament. Do you get embarrassed sometimes when you hear the album, when you think about how personal it is?

I get embarrassed. You see, sometimes I can hear it and be embarrassed just by the performance of either the music or the statements, and sometimes I don’t. I change daily, you know. Like just before it’s coming out, I can’t bear to hear it in the house or play it anywhere, but a few months before that, I can play it all the time. It just changes all the time. Sometimes I used to listen to something, Buddy Holly or something, and one day the record will sound twice as fast as the next day. Did you ever experience that on a single? I used to have that: one day “Hound Dog” would sound very slow and one day it would sound very fast. It was just my feeling towards it. The way I heard it. It can do that. That’s where you have to make your artistic judgment to say well, this is the take and this isn’t. That’s the way you have to make the decision: when it sounds reasonable. “Isolation” and “Hold On John” are rough remixes. I just mixed them on 7 1/2 [ips, a conventional home tape recorder speed] to take home to play and see what else I was going to do with them. Then I didn’t even put them onto 15 [ips – the speed at which professional taping is done], so the quality is a bit off on them. What is your concept of pain?

I don’t know what you mean, really. On the song “God” you start by saying: “God is a concept by which we measure our pain. . . . “

Well, pain is the pain we go through all the time. You’re born in pain. Pain is what we are in most of the time, and I think that the bigger the pain, the more God you look for. There is a tremendous body of philosophical literature about God as a measure of pain.

I never heard of it. You see, it was my own revelation. I don’t know who wrote about it, or what anybody else said, I just know that’s what I know. Yoko: He just felt it. John: Yes, I just felt it. It was like I was crucified, when I felt it. So I know what they’re talking about now. What is the difference between George Martin and Phil Spector?

George Martin . . . I don’t know. You see, for quite a few of our albums, like the Beatles’ double albums, George Martin didn’t really produce it. In the early days, I can remember what George Martin did. What did he do in the early days?

He would translate . . . If Paul wanted to use violins he would translate it for him. Like “In My Life” there is an Elizabethan piano solo in it, so he would do things like that. We would say “play like Bach” or something, so he would put 12 bars in there. He helped us develop a language, to talk to musicians. I was very, very shy, and there are many reasons why I didn’t like very much go for musicians. I didn’t like to have to see 20 guys sitting there and try to tell them what to do. Because they’re all so lousy anyway. So, apart from the early days – when I didn’t have much to do with it – I did it myself. Why did you use Phil now instead of George Martin?

Well it’s not instead of George Martin. That’s nothing personal against George Martin. He’s more Paul’s style of music than mine. But I don’t know, really . . . it’s a drag to do both. To go in the recording studio and then you run back and say did you get it? Did Phil make any special contribution?

Yes, yes. Phil, I believe, is a great artist and like all great artists he’s very neurotic. But we’ve done quite a few tracks together, Yoko and I, and she’d be encouraging me in the other room and all that, and – at one point in the middle we were just lagging – Phil moved in and brought in a new life. We were getting heavy because we had done a few things and the thrill of recording had worn off a little. So you can hear Spector here and there. There is no specifics, you can just hear him. I read a little interview with you done when you went to the Rock and Roll Revival over a year ago in Toronto. You said you were throwing up before you went on stage.

Yes. I just threw up for hours until I went on. I even threw up . . . I read a review in Stone, the one about the film [Toronto Pop, by D.A. Pennebaker] I haven’t seen yet, and they were saying I was this and that. I was throwing up nearly in the number, I could hardly sing any of them, I was full of shit. Would you still be that nervous if you appeared in public?

Always that nervous, but what with one thing and another, it just had to come out some way. I don’t think I’ll do much appearing, it’s not worth the strain, I don’t want to perform too much for people. What do you think of George’s album?

I don’t know . . . I think it’s all right, you know. Personally, at home, I wouldn’t play that kind of music, I don’t want to hurt George’s feelings, I don’t know what to say about it. I think it’s better than Paul’s. What did you think of Paul’s?

I thought Paul’s was rubbish. I think he’ll make a better one, when he’s frightened into it. But I thought that first one was just a lot of . . . Remember what I told you when it came out? “Light and easy,” You know that crack. But then I listen to the radio and I hear George’s stuff coming over, well then it’s pretty bloody good. My personal tastes are very strange, you know. What are your personal tastes?

Sounds like “Wop Bop a Loo Bop.” I like rock and roll, man, I don’t like much else. Why rock and roll?

That’s the music that inspired me to play music. There is nothing conceptually better than rock and roll. No group, be it Beatles. Dylan or Stones have ever improved on “Whole Lot of Shaking” for my money. Or maybe I’m like our parents: that’s my period and I dig it and I’ll never leave it. What do you think of the rock and roll scene today?

I don’t know what it is. You would have to name it. I don’t think there’s. . . . Do you get any pleasure out of the Top Ten?

No, I never listen. Only when I’m recording or about to bring something out will I listen. Just before I record, I go buy a few albums to see what people are doing. Whether they have improved any, or whether anything happened. And nothing’s really happened. There’s a lot of great guitarists and musicians around, but nothing’s happening, you know. I don’t like the Blood, Sweat and Tears shit. I think all that is bullshit. Rock and roll is going like jazz, as far as I can see, and the bullshitters are going off into that excellentness which I never believed in and others going off … I consider myself in the avant garde of rock and roll. Because I’m with Yoko and she taught me a lot and I taught her a lot, and I think on her album you can hear it, if I can get away from her album for a moment. What do you think of Dylan’s album?

I thought it wasn’t much. Because I expect more – maybe I expect too much from people – but I expect more. I haven’t been a Dylan follower since he stopped rocking. I liked “Rolling Stone” and a few things he did then; I like a few things he did in the early days. The restof it is just like Lennon-McCartney or something. It’s no different, its a myth. You don’t think then it’s a legitimate “New Morning”?

No, It might be a new morning for him because he stopped singing on the top of his voice. It’s all right, but it’s not him, it doesn’t mean a fucking thing. I’d sooner have “I Hear You Knocking” by Dave Edmonds, it’s the top of England now. It’s strange that George comes out with his “Hare Krishna” and you come out with the opposite, especially after that.

I can’t imagine what George thinks. Well, I suppose he thinks I’ve lost the way or something like that. But to me, I’m like home. I’ll never change much from this. Let’s re-approach that: always the Beatles were talked about – and the Beatles talked about themselves – as being four parts of the same person. What’s happened to those four parts?

They remembered that they were four individuals. You see, we believed the Beatles myth, too. I don’t know whether the others still believe it. We were four guys . . . I met Paul, and said, “You want to join me band?” Then George joined and then Ringo joined. We were just a band that made it very, very, big that’s all. Our best work was never recorded. Why?

Because we were performers – in spite of what Mick says about us – in Liverpool, Hamburg and other dance halls. What we generated was fantastic, when we played straight rock, and there was nobody to touch us in Britain. As soon as we made it, we made it, but the edges were knocked off. You know Brian put us in suits and all that, and we made it very, very big. But we sold out, you know. The music was dead before we even went on the theater tour of Britain. We were feeling shit already, because we had to reduce an hour or two hours’ playing, which we were glad about in one way, to 20 minutes, and we would go on and repeat the same 20 minutes every night. The Beatles music died then, as musicians. That’s why we never improved as musicians; we killed ourselves then to make it. And that was the end of it. George and I are more inclined to say that; we always missed the club dates because that’s when we were playing music, and then later on we became technically, efficient recording artists – which was another thing – because we were competent people and whatever media you put us in we can produce something worthwhile. How did you choose the musicians you use on this record?

I’m a very nervous person, really, I’m not as big-headed as this tape sounds, this is me projecting through the fear, so I choose people that I know, rather than strangers. Why do you get along with Ringo?

Because in spite of all the things, the Beatles could really play music together when they weren’t uptight, and if I get a thing going, Ringo knows where to go, just like that, and he does well. We’ve played together so long, that it fits. That’s the only thing I sometimes miss is just being able to sort of blink or make a certain noise and I know they’ll all know where we are going on an ad lib thing. But I don’t miss it that much. How do you rate yourself as a guitarist?

Well, it depends on what kind of guitarist. I’m OK, I’m not technically good, but I can make it fucking howl and move. I was rhythm guitarist. It’s an important job. I can make a band drive. How do you rate George?

He’s pretty good. (Laughter) I prefer myself. I have to be honest, you know. I’m really very embarrassed about my guitar playing, in one way, because it’s very poor, I can never move, but I can make a guitar speak. I think there’s a guy called Richie Valens, no, Richie Havens, does he play very strange guitar? He’s a black guy that was on a concert and sang “Strawberry Fields” or something. He plays like one chord all the time. He plays a pretty funky guitar. But he doesn’t seem to be able to play in the real terms at all. I’m like that. Yoko has made me feel cocky about my guitar. You see, one part of me says yes, of course I can play because I can make a rock move, you know. But the other part of me says well, I wish I could just do like B. B. King. If you would put me with B. B. King, I would feel real silly. I’m an artist, and if you give me a tuba, I’ll bring you something out of it. You say you can make the guitar speak; what songs have you done that on?

Listen to “Why” on Yoko’s album I Found Out. I think it’s nice. It drives along. Ask Eric Clapton, he thinks I can play, ask him. You see, a lot of you people want technical things; it’s like wanting technical films. Most critics of rock and roll, and guitarists, are in the stage of the Fifties when they wanted a technically perfect film, finished for them, and then they would feel happy. I’m a cinema verite guitarist, I’m a musician and you have to break down your barriers to hear what I’m playing. There’s a nice little bit I played, they had it on the back of Abbey Road. Paul gave us each a piece, there is a little break where Paul plays, George plays and I played. And there is one bit, one of those where it stops, one of those “carry that weights” where it suddenly goes boom, boom, on the drums and then we all take it in turns to play. I’m the third one on it. I have a definite style of playing. I’ve always had. But I was over-shadowed. They call George the invisible singer. I’m the invisible guitarist. You said you played slide guitar on “Get Back.”

Yes, I played the solo on that. When Paul was feeling kindly, he would give me a solo! Maybe if he was feeling guilty that he had most of the “A” side or something, he would give me a solo. And I played the solo on that. I think George produced some beautiful guitar playing. But I think he’s too hung up to really let go, but so is Eric, really. Maybe he’s changed. They’re all so hung up. We all are, that’s the problem. I really like B. B. King. Do you like Ringo’s record, his country one?

I think it’s a good record. I wouldn’t buy any of it, you know. I think it’s a good record, and I was pleasantly surprised to hear “Beaucoups of Blues,” that song you know. I thought, good. I was glad, and I didn’t feel as embarrassed as I did about his first record. It’s hard when you ask me, it’s like asking me what do I think of . . . ask me about other people, because it looks so awful when I say I don’t like this and I don’t like that. It’s just that I don’t like many of the Beatles records either. My own taste is different from that which I’ve played sometimes, which is called “cop out” to make money or whatever. Or because I didn’t know any better. I would like to ask a question about Paul and go through that. When we went and saw Let It Be in San Francisco, what was your feeling?

I felt sad, you know. Also I felt . . . that film was set-up by Paul for Paul. That is one of the main reasons the Beatles ended. I can’t speak for George, but I pretty damn well know we got fed up of being side-men for Paul. After Brian died, that’s what happened, that’s what began to happen to us. The camera work was set-up to show Paul and not anybody else. And that’s how I felt about it. On top of that, the people that cut it, did it as if Paul is God and we are just lyin’ around there. And that’s what I felt. And I knew there were some shots of Yoko and me that had been just chopped out of the film for no other reason than the people were oriented for Englebert Humperdinck. I felt sick. How would you trace the break-up of the Beatles?

After Brian died, we collapsed. Paul took over and supposedly led us. But what is leading us, when we went round in circles? We broke up then. That was the disintegration. When did you first feel that the Beatles had broken up? When did that idea first hit you?

I don’t remember, you know. I was in my own pain. I wasn’t noticing, really. I just did it like a job. The Beatles broke up after Brian died; we made the double album, the set. It’s like if you took each track off it and made it all mine and all George’s. It’s like I told you many times, it was just me and a backing group, Paul and a backing group, and I enjoyed it. We broke up then. Where were you when Brian died?

We were in Wales with the Maharishi. We had just gone down after seeing his lecture first night. We heard it then, and then we went right off into the Maharishi thing. Where were you?

In Wales. A place called Bangor, in Wales. Were you in a hotel or what?

We were just outside a lecture hall with Maharishi and I don’t know . . . I can’t remember, it just sort of came over. Somebody came up to us . . . the press were there, because we had gone down with this strange Indian, and they said “Brian’s dead” and I was stunned, we went in to him. “What, he’s dead,” and all were, I suppose, and the Marharishi, we went in to him. “What, he’s dead,” and all that, and he was sort of saying oh, forget it, be happy, like an idiot, like parents, smile, that’s what the Maharishi said. And we did. What was your feeling when Brian died?

The feeling that anybody has when somebody close to them dies. There is a sort of little hysterical, sort of hee, hee, I’m glad it’s not me or something in it, the funny feeling when somebody close to you dies. I don’t know whether you’ve had it, but I’ve had a lot of people die around me and the other feeling is, “What the fuck? What can I do?” I knew that we were in trouble then. I didn’t really have any misconceptions about our ability to do anything other than play music and I was scared. I thought, “We’ve fuckin’ had it.” What were the events that sort of immediately happened after Brian died?

Well, we went with Maharishi . . . I remember being in Wales and then, I can’t remember though. I will probably have to have a bloody primal to remember this. I don’t remember. It just all happened. How did Paul react?

I don’t know how the others took it, it’s no good asking me . . . it’s like asking me how you took it. I don’t know. I’m in me own head, I can’t be in anybody else’s. I don’t know really what George, Paul or Ringo think anymore. I know them pretty well, but I don’t know anybody that well. Yoko, I know about the best. I don’t know how they felt. It was my own thing. We were all just dazed. So Brian died and then you said what happened was that Paul started to take over.

That’s right. I don’t know how much of this I want to put out. Paul had an impression, he has it now like a parent, that we should be thankful for what he did for keeping the Beatles going. But when you look back upon it objectively, he kept it going for his own sake. Was it for my sake Paul struggled? Paul made an attempt to carry on as if Brian hadn’t died by saying, “Now, now, boys, we’re going to make a record.” Being the kind of person I am, I thought well, we’re going to make a record all right, so I’ll go along, so we went and made a record. And that’s when we made Magical Mystery Tour. That was the real . . . Paul had a tendency to come along and say well he’s written these ten songs, let’s record now. And I said, “well, give us a few days, and I’ll knock a few off,” or something like that. Magical Mystery Tour was something he had worked out with Mal and he showed me what his idea was and this is how it went, it went around like this, the story and how he had it all . . . the production and everything. Paul said, “Well, here’s the segment, you write a little piece for that,” and I thought bloody hell, so I ran off and I wrote the dream sequence for the fat woman and all the thing with the spaghetti. Then George and I were sort of grumbling about the fuckin’ movie and we thought we better do it and we had the feeling that we owed it to the public to do these things. When did your songwriting partnership with Paul end?

That ended . . . I don’t know, around 1962, or something, I don’t know. If you give me the albums I can tell you exactly who wrote what, and which line. We sometimes wrote together. All our best work – apart from the early days, like “I Want to Hold Your Hand” we wrote together and things like that – we wrote apart always. The “One After 909,” on the Let It Be LP, I wrote when I was 17 or 18. We always wrote separately, but we wrote together because we enjoyed it a lot sometimes, and also because they would say well, you’re going to make an album get together and knock off a few songs, just like a job. Whose idea was it to go to India?

I don’t know . . . I don’t know, probably George’s, I have no idea. Yoko and I met around then. I lost me nerve because I was going to take me ex-wife and Yoko, but I don’t know how to work it. So I didn’t quite do it. “Sexy Sadie” you wrote about the Maharishi?

That’s about the Maharishi, yes. I copped out and I wouldn’t write “Maharishi what have you done, you made a fool of everyone.” But, now it can be told, Fab Listeners. When did you realize he was making a fool of you?

I don’t know, I just sort of saw him. While in India or when you got back?

Yes, there was a big hullaballo about him trying to rape Mia Farrow or somebody and trying to get off with a few other women and things like that. We went to see him, after we stayed up all night discussing was it true or not true. When George started thinking it might be true, I thought well, it must be true; because if George started thinking it might be true, there must be something in it. So we went to see Maharishi, the whole gang of us, the next day, charged down to his hut, his bungalow, his very rich-looking bungalow in the mountains, and as usual, when the dirty work came, I was the spokesman – whenever the dirty work came, I actually had to be leader, wherever the scene was, when it came to the nitty gritty, I had to do the speaking – and I said “We’re leaving.” “Why?” he asked, and all that shit and I said, “Well, if you’re so cosmic, you’ll know why.” He was always intimating, and there were all these right-hand men always intimating, that he did miracles. And I said, “You know why,” and he said, “I don’t know why, you must tell me,” and I just kept saying “You ought to know” and he gave me a look like, “I’ll kill you, you bastard,” and he gave me such a look. I knew then. I had called his bluff and I was a bit rough to him. Yoko: You expected too much from him. John: I always do, I always expect too much. I was always expecting my mother and never got her. That’s what it is, you know, or some parent, I know that much. You came to New York and had that press conference.

The Apple thing. That was to announce Apple. But at the same time you disassociated yourselves from the Maharishi.

I don’t remember that. You know, we all say a lot of things when we don’t know what we’re talking about. I’m probably doing it now, I don’t know what I say. You see, everybody takes you up on the words you said, and I’m just a guy that people ask all about things, and I blab off and some of it makes sense and some of it is bullshit and some of it’s lies and some of it is – God knows what I’m saying. I don’t know what I said about Maharishi, all I know is what we said about Apple, which was worse. Will you talk about Apple?

All right. How did that start?

Clive Epstein, or some other such business freak, came up to us and said you’ve got to spend so much money, or the tax will take you. We were thinking of opening a chain of retail clothes shops or some balmy thing like that . . . and we were all thinking that if we are going to have to open a shop, let’s open something we’re interested in, and we went through all these different ideas about this, that and the other. Paul had a nice idea about opening up white houses, where we would sell white china, and things like that, everything white, because you can never get anything white, you know, which was pretty groovy, and it didn’t end up with that, it ended up with Apple and all this junk and The Fool and all those stupid clothes and all that. What happened to Magic Alex?

I don’t know, he’s still in London. Did you all really think he had those inventions?

I think some of his stuff actually has come true, but they just haven’t been manufactured – maybe one of them is a salable object. He was just another guy. who comes and goes around people like us. He’s all, right, but he’s cracked, you know. When did you decide to close that down?

I don’t know. I was controlling the scene at the time, I mean, I was the one going in the office and shouting about. Paul had done it for six months, and then I walked in and changed everything. There were all the Peter Browns reporting behind my back to Paul, saying, “You know, John’s doing this and John’s doing that, that John, he’s crazy,” I was always the one that must be crazy, because I wouldn’t let them have status quo. Well, Yoko and I together, we came up with the idea to give it all away, and stop fuckin’ about with a psychedelic clothes shop, so we gave it all away. It was a good happening. Were you at the big giveaway?

No, we read it in the papers. That was when we started events. I learned events from Yoko. We made everything into events from then on and got rid of it. You gave away your M.B.E.?

I’d been planning on it for over a year and a bit. I was waiting for a time to do it. You said then that you were waiting to tag it to some event, then you realized that it was the event.

That’s the truth. You also said then that you had another thing you were going to do.

I don’t know what it was. Do you remember?

Yes, I do. Well, we always had . . . we always kept them on their toes, during our events period. I don’t know, but we said we had some other surprise for them later. I can’t remember what it was. Yoko: Probably War Is Over, the poster event. To go back to Apple and the breakup of the Beatles, Brian died, and one thing and another. . . .

I didn’t really want to talk about all this . . . go on. Do you mind?

Well, we’re half-way through it now, so let’s do it. You said you quit the Beatles first.

Yes. How?

I said to Paul “I’m leaving.” I knew on the flight over to Toronto or before we went to Toronto: I told Allen I was leaving, I told Eric Clapton and Klaus that I was leaving then, but that I would probably like to use them as a group. I hadn’t decided how to do it – to have a permanent new group or what – then later on, I thought fuck, I’m not going to get stuck with another set of people, whoever they are. I announced it to myself and the people around me on the way to Toronto a few days before. And on the plane – Klein came with me – I told Allen, “It’s over.” When I got back, there were a few meetings, and Allen said well, cool it, cool it, there was a lot to do, businesswise you know, and it would not have been suitable at the time. Then we were discussing something in the office with Paul, and Paul said something or other about the Beatles doing something, and I kept saying “No, no, no” to everything he said. So it came to a point where I had to say something, of course, and Paul said, “What do you mean?” I said, “I mean the group is over, I’m leaving.” Allen was there, and he will remember exactly and Yoko will, but this is exactly how I see it. Allen was saying don’t tell. He didn’t want me to tell Paul even. So I said, “It’s out,” I couldn’t stop it, it came out. Paul and Allen both said that they were glad that I wasn’t going to announce it, that I wasn’t going to make an event out of it. I don’t know whether Paul said “Don’t tell anybody,” but he was darned pleased that I wasn’t going to. He said, “Oh, that means nothing really happened if you’re not going to say anything.” So that’s what happened. So, like anybody when you say divorce, their face goes all sorts of colors. It’s like he knew really that this was the final thing; and six months later he comes out with whatever. I was a fool not to do it, not to do what Paul did, which was use it to sell a record. You were really angry with Paul?

No, I wasn’t angry. Well, when he came out with this “I’m leaving.”

No, I wasn’t angry – shit, he’s a good P.R. man, that’s all. He’s about the best in the world, probably. He really does a job. I wasn’t angry. We were all hurt that he didn’t tell us that was what he was going to do. I think he claims that he didn’t mean that to happen but that’s bullshit. He called me in the afternoon of that day and said, “I’m doing what you and Yoko were doing last year.” I said good, you know, because that time last year they were all looking at Yoko and me as if we were strange trying to make our life together instead of being fab, fat myths. So he rang me up that day and said I’m doing what you and Yoko are doing, I’m putting out an album, and I’m leaving the group too, he said. I said good. I was feeling a little strange, because he was saying it this time, although it was a year later, and I said “good,” because he was the one that wanted the Beatles most, and then the midnight papers came out. How did you feel then?

I was cursing, because I hadn’t done it. I wanted to do it, I should have done it. Ah, damn, shit, what a fool I was. But there were many pressures at that time with the Northern Songs fight going on; it would have upset the whole thing, if I would have said that. How did you feel when you found out that Dick James had sold his shares in your own company, Northern Songs? Did you feel betrayed?

Sure I did. He’s another one of those people, who think they made us. They didn’t. I’d like to hear Dick James’ music and I’d like to hear George Martin’s music, please, just play me some. Dick James actually has said that. What?

That he made us. People are under a delusion that they made us, when in fact we made them. How did Dick James tell you that? “Well, I’m. . . . “

He didn’t tell us he did it. It was just a fait accompli. He went and sold his thing to Lew Grade. That’s all we knew. We read it in the paper, I think. What was it like? All those meetings and conferences?

Oh, it was fantastic. It was like this room full of old men smoking and fighting. It’s great. People seem to think that businessmen like Allen, or Grade, or any of them, are a race apart. They play the game the way we play music, and it’s something to see. They play a game, first they have a ritual, then they create. Allen, he’s a very creative guy, you know, he creates situations which create positions for them to move in, they all do it, you know, and it’s a sight to see. We played our part, we both did. What did you do?

With the bankers and things like that? I think Allen could tell you better because I don’t know. Everything seems as though it’s going to be trouble, like you can’t say anything about anybody, because you’re going to get sued, or something like that. Allen will tell you what we did. I did a job on this banker that we were using, and on a few other people, and on the Beatles. What?

How do you describe the job? You know, you know, my job – I maneuver people. That’s what leaders do, and I sit and make situations which will be of benefit to me with other people, it’s as simple as that. I had to do a job to get Allen in Apple. I did a job, so did Yoko. Yoko: You do it with instinct, you know. John: Oh. God, Yoko, don’t say that. Maneuvering is what it is, let’s not be coy about it. It is a deliberate and thought-out maneuver of how to get a situation the way we want it. That’s how life’s about, isn’t it, is it not? Yoko: Well, you’re pretty instinctive. John: Instinctive doesn’t . . . isn’t Dick James – so is Lew Grade – they’re all instinctive, so is he, if it’s instinctive – but it’s maneuvering. There’s nothing ashamed about it. We all do it, it’s just owning up, you know, not going around saying “God Bless you, Brother,” pretending there is no vested interest. Yoko: The difference is that you don’t go down and bullshit and get them. But you just instinctively said that Allen is the guy to jump into it. John: That’s not the thing, the point I’m talking about is creating a situation around Apple and the Beatles in which Allen could come in, that is what I’m talking about, and he wouldn’t have gotten in unless I’d done it, and he wouldn’t have gotten in unless you’d done it, you made the decision, too. How did you get Allen in?

The same as I get anything I want. The same as you get what you want. I’m not telling you; just work at it, get on the phone, a little word here, and a little word there and do it. What was Paul’s reaction?

You see, a lot of people, like the Dick James, Derek Taylors, and Peter Browns, all of them, they think they’re the Beatles, and Neil and all of them. Well, I say fuck ’em, you know, and after working with genius for ten, 15 years they begin to think they’re it. They’re not. Do you think you’re a genius?

Yes, if there is such a thing as one, I am one. When did you first realize that?

When I was about 12. I used to think I must be a genius, but nobody’s noticed. I used to wonder whether I’m a genius or I’m not, which is it? I used to think, well, I can’t be mad, because nobody’s put me away, therefore, I’m a genius. A genius is a form of madness, and we’re all that way, you know, and I used to be a bit coy about it, like my guitar playing. If there is such a thing as genius – which is what . . . what the fuck is it? – I am one, and if there isn’t, I don’t care. I used to think it when I was a kid, writing me poetry and doing me paintings. I didn’t become something when the Beatles made it, or when you heard about me, I’ve been like this all me life. Genius is pain too. How do you feel towards the Beatle people? All of them who used to – some still do – work at Apple, who’ve been around during those years. Neil Aspinal, Mal Evans . . .

I didn’t mention Mal. I said Neil, Peter Brown and Derek. They live in a dream of Beatle past, and everything they do is oriented to that. They also have a warped view of what was happening. I suppose we all do. They must feel now that their lives are inextricably bound up in yours.

Well, they have to grow up then. They’ve only had half their life, and they’ve got another whole half to go; and they can’t go on pretending to be Beatles. That’s where it’s at, I mean when they read this, they’ll think it’s “cracked John,” if it’s in the article, but that’s where it’s at, they live in the past. You see, I presumed that I would just be able to carry on, and bring Yoko into our life, but it seemed that I had to either be married to them or Yoko, and I chose Yoko, and I was right. What were their reactions when you first brought Yoko by?

They despised her. From the very beginning?

Yes, they insulted her and they still do. They don’t even know I can see it, and even when its written down, it will look like I’m just paranoiac or she’s paranoiac. I know, just by the way the publicity on us was handled in Apple, all of the two years we were together, and the attitude of people to us and the bits we hear from office girls. We know, so they can go stuff themselves. Yoko: In the beginning, we were too much in love to notice anything. John: We were in our own dream, but they’re the kind of idiots that really think that Yoko split the Beatles, or Allen. It’s the same joke, really, they are that insane about Allen, too. How would you characterize George’s, Paul’s and Ringo’s reaction to Yoko?

It’s the same. You can quote Paul, it’s probably in the papers, he said it many times at first he hated Yoko and then he got to like her. But, it’s too late for me. I’m for Yoko. Why should she take that kind of shit from those people? They were writing about her looking miserable in the Let It Be film, but you sit through 60 sessions with the most bigheaded, up-tight people on earth and see what its fuckin’ like and be insulted – just because you love someone – and George, shit, insulted her right to her face in the Apple office at the beginning, just being ‘straight-forward,’ you know that game of ‘I’m going to be up front,’ because this is what we’ve heard and Dylan and a few people said she’d got a lousy name in New York, and you give off bad vibes. That’s what George said to her! And we both sat through it. I didn’t hit him, I don’t know why. I was always hoping that they would come around. I couldn’t believe it, and they all sat there with their wives, like a fucking jury and judged us and the only thing I did was write that piece (Rolling Stone, April 16th, 1970) about “some of our beast friends” in my usual way – because I was never honest enough, I always had to write in that gobbly-gook – and that’s what they did to us. Ringo was all right, so was Maureen, but the other two really gave it to us. I’ll never forgive them, I don’t care what fuckin’ shit about Hare Krishna and God and Paul with his “Well, I’ve changed me mind.” I can’t forgive ’em for that, really. Although I can’t help still loving them either. Yoko played me tapes I understood. I know it was very strange, and avant garde music is a very tough thing to assimilate and all that, but I’ve heard the Beatles play avant garde music – when nobody was looking – for years. But the Beatles were artists, and all artists have fuckin’ big egos, whether they like to admit it or not, and when a new artist came into the group, they were never allowed. Sometimes George and I would have liked to have brought somebody in like Billy Preston, that was exceptional, we might have had him in the group. We were fed up with the same old shit, but it wasn’t wanted. I would have expanded the Beatles and broken them and gotten their pants off and stopped them being God, but it didn’t work, and Yoko was naive, she came in and she would expect to perform with them, with any group, like you would with any group, she was jamming, but there would be a sort of coldness about it. That’s when I decided: I could no longer artistically get anything out of the Beatles and here was someone that could turn me on to a million things. You say that the dream is over. Part of the dream was that the Beatles were God or that the Beatles were the messengers of God, and of course yourself as God. . . .

Yeah. Well, if there is a God, we’re all it. When did you first start getting the reactions from people who listened to the records, sort of the spiritual reaction?

There is a guy in England, William Mann, who was the first intellectual who reviewed the Beatles in the Times and got people talking about us in that intellectual way. He wrote about Aeolian Cadences and all sorts of musical terms, and he is a bullshitter. But he made us credible with intellectuals. He wrote about Paul’s last album as if it were written by Beethoven or something. He’s still writing the same shit. But it did us a lot of good in that way, because people in all the middle classes and intellectuals were all going “Oooh.” When did somebody first come up to you about this thing about John Lennon as God?

About what to do and all of that? Like “you tell us Guru”? Probably after acid. Maybe after Rubber Soul. I can’t remember it exactly happening. We just took that position. I mean, we started putting out messages. Like “The Word Is Love” and things like that. I write messages, you know. See, when you start putting out messages, people start asking you “what’s the message?” How did you first get involved in LSD?

A dentist in London laid it on George, me and wives, without telling us, at a dinner party at his house. He was a friend of George’s and our dentist at the time, and he just put it in our coffee or something. He didn’t know what it was; it’s all the same thing with that sort of middle class London swinger, or whatever. They had all heard about it, and they didn’t know it was different from pot or pills and they gave us it. He said “I advise you not to leave,” and we all thought he was trying to keep us for an orgy in his house, and we didn’t want to know, and we went to the Ad Lib and these discotheques and there were these incredible things going on. It was insane going around London. When we went to the club we thought it was on fire and then we thought it was a premiere, and it was just an ordinary light outside. We thought, “Shit, what’s going on here?” We were cackling in the streets, and people were shouting “Let’s break a window,” you know, it was just insane. We were just out of our heads. When we finally got on the lift [an elevator in England] we all thought there was a fire, but there was just a little red light. We were all screaming like that, and we were all hot and hysterical, and when we all arrived on the floor, because this was a discotheque that was up a building, the lift stopped and the door opened and we were all [John demonstrates by screaming]. I had read somebody describing the effects of opium in the old days and I thought “Fuck! It’s happening,” and then we went to the Ad Lib and all of that, and then some singer came up to me and said, “Can I sit next to you?” And I said, “Only if you don’t talk,” because I just couldn’t think. This seemed to go on all night. I can’t remember the details. George somehow or another managed to drive us home in his mini. We were going about ten miles an hour, but it seemed like a thousand and Patty was saying let’s jump out and play football. I was getting all these sort of hysterical jokes coming out like speed, because I was always on that, too. God, it was just terrifying, but it was fantastic. I did some drawings at the time, I’ve got them somewhere, of four faces saying “We all agree with you!” I gave them to Ringo, the originals. I did a lot of drawing that night. And then George’s house seemed to be just like a big submarine, I was driving it, they all went to bed, I was carrying on in it, it seemed to float above his wall which was 18 foot and I was driving it. When you came down what did you think?

I was pretty stoned for a month or two. The second time we had it was in L.A. We were on tour in one of those houses, Doris Day’s house or wherever it was we used to stay, and the three of us took it, Ringo, George and I. Maybe Neil and a couple of the Byrds – what’s his name, the one in the Stills and Nash thing, Crosby and the other guy, who used to do the lead. McGuinn. I think they came, I’m not sure, on a few trips. But there was a reporter, Don Short. We were in the garden, it was only our second one and we still didn’t know anything about doing it in a nice place and cool it. Then they saw the reporter and thought “How do we act?” We were terrified waiting for him to go, and he wondered why we couldn’t come over. Neil, who never had acid either, had taken it and he would have to play road manager, and we said go get rid of Don Short, and he didn’t know what to do. Peter Fonda came, and that was another thing. He kept saying [in a whisper] “I know what it’s like to be dead,” and we said “What?” and he kept saying it. We were saying “For Christ’s sake, shut up, we don’t care, we don’t want to know,” and he kept going on about it. That’s how I wrote “She Said, She Said” – “I know what’s it’s like to be dead.” It was a sad song, an acidy song I suppose. “When I was a little boy” … you see, a lot of early childhood was coming out, anyway. So LSD started for you in 1964: How long did it go on?

It went on for years, I must of had a thousand trips. Literally a thousand, or a couple of hundred?

A thousand. I used to just eat it all the time. I never took it in the studio. Once I thought I was taking some uppers and I was not in the state of handling it, I can’t remember what album it was, but I took it and I just noticed . . . I suddenly got so scared on the mike. I thought I felt ill, and I thought I was going to crack. I said I must get some air. They all took me upstairs on the roof and George Martin was looking at me funny, and then it dawned on me I must have taken acid. I said, “Well I can’t go on, you’ll have to do it and I’ll just stay and watch.” You know I got very nervous just watching them all. I was saying, “Is it all right?” And they were saying, “Yeah.” They had all been very kind and they carried on making the record. The other Beatles didn’t get into LSD as much as you did?

George did. In L.A. the second time we took it, Paul felt very out of it, because we are all a bit slightly cruel, sort of “we’re taking it, and you’re not.” But we kept seeing him, you know. We couldn’t eat our food, I just couldn’t manage it, just picking it up with our hands. There were all these people serving us in the house and we were knocking food on the floor and all of that. It was a long time before Paul took it. Then there was the big announcement. Right.

So, I think George was pretty heavy on it; we are probably the most cracked. Paul is a bit more stable than George and I. And straight?

I don’t know about straight. Stable. I think LSD profoundly shocked him, and Ringo. I think maybe they regret it. Did you have many bad trips?

I had many. Jesus Christ, I stopped taking it because of that. I just couldn’t stand it. You got too afraid to take it?

It got like that, but then I stopped it for I don’t know how long, and then I started taking it again just before I met Yoko. Derek came over and . . . you see, I got the message that I should destroy my ego and I did, you know. I was reading that stupid book of Leary’s; we were going through a whole game that everybody went through, and I destroyed myself. I was slowly putting myself together round about Maharishi time. Bit by bit over a two-year period, I had destroyed me ego. I didn’t believe I could do anything and let people make me, and let them all just do what they wanted. I just was nothing. I was shit. Then Derek tripped me out at his house after he got back from L.A. He sort of said “You’re all right,” and pointed out which songs I had written. “You wrote this,” and “You said this” and “You are intelligent, don’t be frightened.” The next week I went to Derek’s with Yoko and we tripped again, and she filled me completely to realize that I was me and that’s it’s all right. That was it; I started fighting again, being a loudmouth again and saying, “I can do this, “fuck it, this is what I want, you know, I want it and don’t put me down.” I did this, so that’s where I am now. At some point, right between Help and Hard Day’s Night, you got into drugs and got into doing drug songs?

A Hard Day’s Night I was on pills, that’s drugs, that’s bigger drugs than pot. Started on pills when I was 15, no, since I was 17, since I became a musician. The only way to survive in Hamburg, to play eight hours a night, was to take pills. The waiters gave you them – the pills and drink. I was a fucking dropped-down drunk in art school. Help was where we turned on to pot and we dropped drink, simple as that. I’ve always needed a drug to survive. The others, too, but I always had more, more pills, more of everything because I’m more crazy probably. There’s a lot of obvious LSD things you did in the music.

Yes. How do you think that affected your conception of the music? In general.

It was only another mirror. It wasn’t a miracle. It was more of a visual thing and a therapy, looking at yourself a bit. It did all that. You know, I don’t quite remember. But it didn’t write the music, neither did Janov or Maharishi in the same terms. I write the music in the circumstances in which I’m in, whether its on acid or in the water. What did you think of A Hard Day’s Night?

The story wasn’t bad but it could have been better. Another illusion was that we were just puppets and that these great people, like Brian Epstein and Dick Lester, created the situation and made this whole fuckin’ thing, and precisely because we were what we were, realistic. We didn’t want to make a fuckin’ shitty pop movie, we didn’t want to make a movie that was going to be bad, and we insisted on having a real writer to write it. Brian came up with Allan Owen, from Liverpool, who had written a play for TV called “No Trams to Lime St.” Lime Street is a famous street in Liverpool where the whores used to be in the old days, and Owen was famous for writing Liverpool dialogue. We auditioned people to write for us and they came up with this guy. He was a bit phony, like a professional Liverpool man – you know like a professional American. He stayed with us two days, and wrote the whole thing based on our characters then: me, witty; Ringo, dumb and cute; George this; and Paul that. We were a bit infuriated by the glibness and shiftiness of the dialogue and we were always trying to get it more realistic, but they wouldn’t have it. It ended up O.K., but the next one was just bullshit, because it really had nothing to do with the Beatles. They just put us here and there. Dick Lester was good, he had ideas ahead of their times, like using Batman comic strip lettering and balloons. My impression of the movie was that it was you and it wasn’t anyone else.

It was a good projection of one facade of us, which was on tour, once in London and once in Dublin. It was of us in that situation together, in a hotel, having to perform before people. We were like that. The writer saw the press conference. Rubber Soul was . . .

Can you tell me whether that white album with the drawing by Voorman on it, was that before Rubber Soul or after? After. You really don’t remember which?

No, maybe the others do, I don’t remember those kind of things, because it doesn’t mean anything, it’s all gone. Rubber Soul was the first attempt to do a serious, sophisticated complete work, in a certain sense.

We were just getting better, technically and musically, that’s all. Finally we took over the studio. In the early days, we had to take what we were given, we didn’t know how you can get more bass. We were learning the technique on Rubber Soul. We were more precise about making the album, that’s all, and we took over the cover and everything. Rubber Soul, that was just a simple play on . . .

That was Paul’s title, it was like “Yer Blues,” I suppose, meaning English Soul, I suppose, just a pun. There is no great mysterious meaning behind all of this, it was just four boys working out what to call a new album. The Hunter Davies book, the “authorized biography,” says . . .

It was written in [London] Sunday Times sort of fab form. And no home truths was written. My auntie knocked out all the truth bits from my childhood and my mother and I allowed it, which was my cop-out, etcetera. There was nothing about orgies and the shit that happened on tour. I wanted a real book to come out, but we all had wives and didn’t want to hurt their feelings. End of that one. Because they still have wives. The Beatles tours were like the Fellini film Satyricon. We had that image. Man, our tours were like something else, if you could get on our tours, you were in. They were Satyricon, all right. Would you go to a town . . . a hotel . . .

Wherever we went, there was always a whole scene going, we had our four separate bedrooms. We tried to keep them out of our room. Derek’s and Neil’s rooms were always full of junk and whores and who-the-fuck-knows-what, and policemen with it. Satyricon! We had to do something. What do you do when the pill doesn’t wear off and it’s time to go? I used to be up all night with Derek, whether there was anybody there or not, I could never sleep, such a heavy scene it was. They didn’t call them groupies then, they called it something else and if we couldn’t get groupies, we would have whores and everything, whatever was going. Who would arrange all that stuff?

Derek and Neil, that was their job, and Mal, but I’m not going into all that. Like businessmen at a convention.

When we hit town, we hit it. There was no pissing about. There’s photographs of me crawling about in Amsterdam on my knees coming out of whore houses and things like that. The police escorted me to the places, because they never wanted a big scandal, you see. I don’t really want to talk about it, because it will hurt Yoko. And it’s not fair. Suffice to say, that they were Satyricon on tour and that’s it, because I don’t want to hurt their feelings, or the other people’s girls either. It’s just not fair. Yoko: I was surprised, I really didn’t know things like that. I thought well, John is an artist, and probably he had two or three affairs before getting married. That is the concept you have in the old school. New York artists group, you know, that kind. The generation gap.

Right, right, exactly. Let me ask you about something else that was in the Hunter Davies book. At one point it said you and Brian Epstein went off to Spain.

Yes. We didn’t have an affair though. Fuck knows what was said. I was pretty close to Brian. If somebody is going to manage me, I want to know them inside out. He told me he was a fag. I hate the way Allen is attacked and Brian is made out to be an angel just because he’s dead. He wasn’t, you know, he was just a guy. What else was left out of the Hunter Davies book?

That I don’t know, because I can’t remember it. There is a better book on the Beatles by Michael Brown, Love Me Do. That was a true book. He wrote how we were, which was bastards. You can’t be anything else in such a pressurized situation and we took it out on people like Neil, Derek and Mal. That’s why underneath their facade, they resent us, but they can never show it, and they won’t believe it when they read it. They took a lot of shit from us, because we were in such a shitty position. It was hard work, and somebody had to take it. Those things are left out by Davies, about what bastards we were. Fuckin’ big bastards, that’s what the Beatles were. You have to be a bastard to make it, that’s a fact, and the Beatles are the biggest bastards on earth. Yoko: How did you manage to keep that clean image? It’s amazing. John: Everybody wants the image to carry on. You want to carry on. The press around too, because they want the free drinks and the free whores and the fun; everybody wants to keep on the bandwagon. We were the Caesars; who was going to knock us, when there were a million pounds to be made? All the handouts, the bribery, the police, all the fucking hype. Everybody wanted in, that’s why some of them are still trying to cling on to this: Don’t take Rome from us, not a portable Rome where we can all have our houses and our cars and our lovers and our wives and office girls and parties and drink and drugs, don’t take it from us, otherwise you’re mad, John, you’re crazy, silly John wants to take this all away. What was it like in the early days in London?

When we came down, we were treated like real provincials by the Londoners. We were in fact, provincials. What was it like, say, running around London, in the discotheques, with the Stones, and everything.

That was a great period. We were like kings of the jungle then, and we were very close to the Stones. I don’t know how close the others were but I spent a lot of time with Brian and Mick. I admire them, you know. I dug them the first time I saw them in whatever that place is they came from, Richmond. I spent a lot of time with them, and it was great. We all used to just go around London in cars and meet each other and talk about music with the Animals and Eric and all that. It was really a good time, that was the best period, fame-wise. We didn’t get mobbed so much. It was like a men’s smoking club, just a very good scene. What was Brian Jones like?

Well, he was different over the years as he disintegrated. He ended up the kind of guy that you dread when he would come on the phone, because you knew it was trouble. He was really in a lot of pain. In the early days, he was all right, because he was young and confident. He was one of them guys that disintegrated in front of you. He wasn’t sort of brilliant or anything, he was just a nice guy. When he died?

By then I didn’t feel anything. I just thought another victim of the drug scene. What do you think of the Stones today?

I think its a lot of hype. I like “Honky Tonk Woman” but I think Mick’s a joke, with all that fag dancing, I always did. I enjoy it, I’ll probably go and see his films and all, like everybody else, but really, I think it’s a joke. Do you see him much now?

No, I never do see him. We saw a bit of each other around when Allen was first coming in – I think Mick got jealous. I was always very respectful about Mick and the Stones, but he said a lot of sort of tarty things about the Beatles, which I am hurt by, because you know, I can knock the Beatles, but don’t let Mick Jagger knock them. I would like to just list what we did and what the Stones did two months after on every fuckin’ album. Every fuckin’ thing we did, Mick does exactly the same – he imitates us. And I would like one of you fuckin’ underground people to point it out, you know Satanic Majesties is Pepper, “We Love You,” it’s the most fuckin’ bullshit, that’s “All You Need Is Love.” I resent the implication that the Stones are like revolutionaries and that the Beatles weren’t. If the Stones were or are, the Beatles really were too. But they are not in the same class, music-wise or power-wise, never were. I never said anything, I always admired them, because I like their funky music and I like their style. I like rock and roll and the direction they took after they got over trying to imitate us, you know, but he’s even going to do Apple now. He’s going to do the same thing. He’s obviously so upset by how big the Beatles are compared with him; he never got over it. Now he’s in his old age, and he is beginning to knock us, you know, and he keeps knocking. I resent it, because even his second fuckin’ record we wrote it for him. Mick said “Peace made money.” We didn’t make any money from Peace. You know. Yoko: We lost money. When Sgt. Pepper came out, did you know that you had put together a great album? Did you feel that while you were making it?

Yeah, yeah and Rubber Soul, too, and Revolver. What did you think of that review in the New York Times of Sgt. Pepper?

I don’t remember it. Did it pan it? Yes.

I don’t remember. In those days reviews weren’t very important, because we had it made whatever happened. Nowadays, I’m as sensitive as shit. But those days, we were too big to touch. I don’t remember the reviews at all, I never read them. We were so blase, we never even read the news clippings. It was a bore to read about us. I don’t even remember ever hearing about that review. They’ve been trying to knock us down since we began, specially the British press, always saying, “What are you going to do when the bubble bursts?” That was the in-crowd joke with us. We’d go when we decided, not when some fickle public decided, because we were not a manufactured group. We knew what we were doing. Of course, we’ve made many mistakes, but we knew instinctively that it would end when we decided, and not when NBC or ATV decides to take off our series, or anything like that. There were very few things that happened to the Beatles that weren’t really well-thought out by us – whether to do it or not, and what the reaction would be and would it last forever. We had an instinct for something like that. But you got busted.

Yeah, but there are two ways of thinking: they are out to get us or it just happened that way. After I started Two Virgins and doing those kind of things, it seemed like I was fair game for the police. There was some myth about us being protected because we had an MBE. I don’t think that it was true, it was just that we never did anything. The way Paul said the acid thing . . . I never got attacked for it, I don’t know whether that was protection, because it was openly admitting that we had drugs. I just think nobody really bothered about us. Why can’t you be alone without Yoko?

I can be, but I don’t wish to be. There is no reason on earth why I should be without her. There is nothing more important than our relationship, nothing. We dig being together all the time, and both of us could survive apart, but what for? I’m not going to sacrifice love, real love, for any fuckin’ whore, or any friend, or any business, because in the end, you’re alone at night. Neither of us want to be, and you can’t fill the bed with groupies. I don’t want to be a swinger. Like I said in the song, I’ve been through it all, and nothing works better than to have somebody you love hold you. You said at one point, you have to write songs that can justify your existence.